By Franziska

In the summer of 2018, three friends and I made a trip through four different countries in Europe by train to celebrate graduating from university. When we arrived in Budapest, our third stop, we left our dingy ten-bed hostel room again immediately to see the city at night and eat by the water. Across the lake we sat by, we could see the Museum of Fine Arts advertising its current exhibition of Frida Kahlo’s works. I had never considered that seeing her original paintings was something I would be able to do; to me, she was simply too big, a larger-than-life icon of unconventional femininity, art, and Mexican culture. As soon as I saw the posters, I informed my friends that we had to go see Frida, since this was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. I felt elated as we entered the museum with numerous other tourists the next day, and although the rooms were packed, I was still gripped by the experience. The moment I remember most vividly from this day—and maybe the entire trip—was standing in front of one of Frida’s self-portraits. It’s called A Broken Column, and it depicts her naked, her entire body split in two, revealing the broken column as her spine. She is strapped together by clinical-looking, white leather belts, nails impaling her whole body, and tears spilling from her eyes. As I stood there among other sweaty tourists, looking up at her, she looked back at me: pained but unwavering. I started crying right there, among all this art she left behind as her legacy. Nobody noticed, which I was thankful for, because I could not have explained my reaction. I am not an art person—I like to look at it, but never before in my life had I felt like crying because of a painting. Still, the tears kept coming as I continued through the exhibition. I joined one of my friends again to look at nude sketches of women, all labelled as Frida’s “close friends.” I knew she had had relationships with both men and women, and when I mentioned it to my friends we laughed, speculating that there might have been more than “close friendship” at play. I have always been bisexual, but at this point in my life, I did not know this about me because I would not let myself. But I saw Frida, who had let herself live it, and she looked back at me.

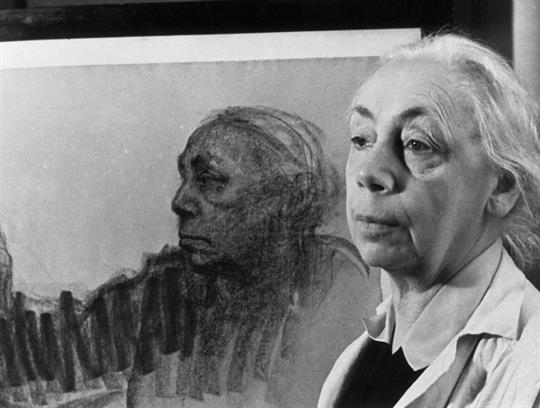

A year later, I had settled into a new university and temporarily moved in with my parents again when a friend asked me to come to the museum with her. She wanted to go to the Käthe Kollwitz Museum in the city we grew up in, and since I had never been, I decided to join her. Käthe Kollwitz is a famous German artist, known for both her sculptures and her paintings. Her art had never clicked with me. I found it depressing, especially the framed print of one of her paintings in my parents’ living room that had been there as long as I could remember. The museum was empty when we arrived, and as we worked our way through the exhibition, I enjoyed the art and history of it more than I expected. I was impressed by the artist’s firm anti-war stance and her passion for workers’ rights. My friend and I ended up drifting to different parts of the exhibition, so I was completely alone when I came across one of her self-portraits from 1910. I stood and stared, and Käthe Kollwitz stared back at me resolutely, one side of her face in darkness and the other one in light, a hand at her temple. There is nothing a person could hide from that stare, and it went right through me. I felt that my eyes were wet and was remined of Frida’s portrait. I couldn’t help but laugh quietly to myself. There I was again, crying in an art gallery for no reason. At least this one was empty. I bought a postcard of the painting on my way out.

As I remembered my first art-related emotional outburst in Budapest, later that day I reflected on the year that had passed since then. During this time, I had come out as bisexual both to myself and some of my friends. It had taken a lot. A lot of back and forth, of bargaining with myself and others, of tears ,and finally an understanding that all of that wasn’t worth it. I could not change this fact about me, and I did not want to deny it anymore. Instead, I now had questions: Who is a bisexual person? What are they like? Where are they? I did not know anybody else who was bi. I felt disconnected from this newly accepted facet of my identity. I remembered Frida Kahlo. I had seen her paintings. I knew what she had done in her life, and I admired her. By accident, I also came across one of Käthe Kollwitz’s lesser-known quotes: “I believe that bisexuality is almost a needed requirement for creating art.”[1] I couldn’t believe my eyes. I checked and double-checked, but it was a real quote. Käthe Kollwitz had fallen in love with people of different genders in her life, and I had never known. She had even used the word “bisexuality” in 1923, almost a hundred years ago. All the years I had been asking myself, “Who is a bisexual person?” her painting hung on my parents’ wall. The fact that it had been there all along makes me smile to this day because somehow, it makes me feel seen in a very private way that is infinitely reassuring. We’ve been here, where you least expect us, and we will be here for decades to come.

I see what Frida and Käthe have given me by just existing and being remembered, and I want to preserve that gift. I also want to take it and multiply it with the strength they have given me to carry on with my own path. They make me want to add on to that legacy, and every time I ask myself what kind of person I have to become to do this, it feels easier to make hard choices, to take chances, and to care for myself in order to preserve my energy to carry on. Their legacy also makes it easier to reach out to people who might share my experience. I am thankful to everybody who has felt the same way about them that I do, and preserved and added to the history of Frida, Käthe, and all our other bisexual, pansexual, plurisexual, and queer role models. Your existence makes me feel a connection through time and space. I would be honored to follow in your footsteps.

[1] From Kollwitz, K. (1999). Die Tagebücher 1908-1943 (ed.) J. Bohnke-Kollwitz (Munich 2012), 435, 725., my translation

Franziska (she/her), a queer history nerd, cries frequently and likes to look at art she doesn’t understand. Sometimes she combines all three.