By Laura Berol

Years ago, when I was a college student and a virgin, my favorite fantasy was of a soft-sided pit, the kind that trampoline parks fill with blue foam blocks or brightly colored balls. In my version, the pit contained naked women, as sleek and lustrous as plastic balls and as soft as foam blocks, gently holding and supporting me. It was the patriarchal ideal of femininity—eternally youthful, infinitely available, simultaneously motherly and erotic, utterly without concern for self-expectations that would become unsupportable when I entered parenthood and middle age. But to the teenage me, learning to inhabit my same-sex desire, this fantasy felt like rebellion against the system, a pure escape.

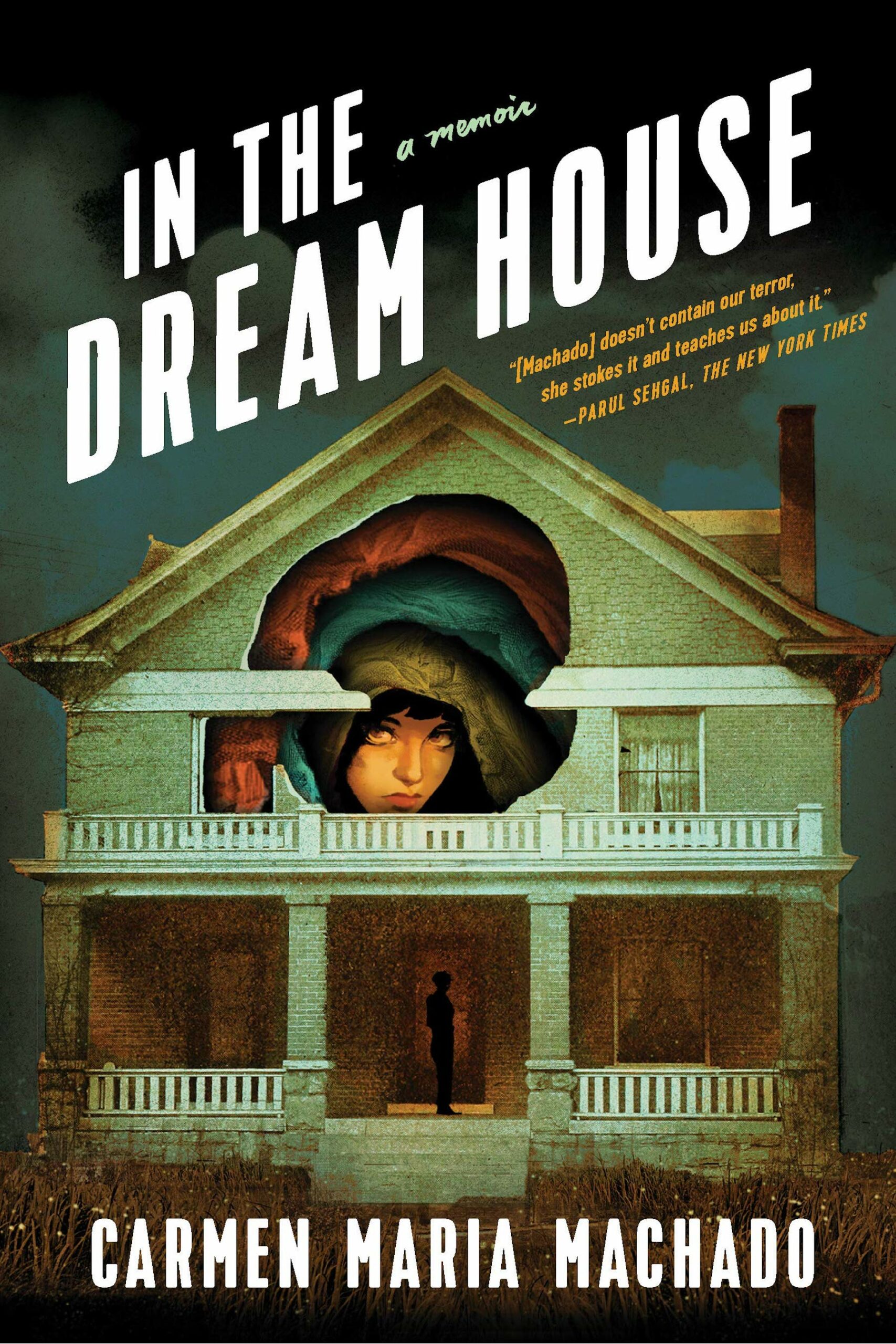

The equivocal character of my teenage fantasy, its dual function as both lock-pick and jail bars, came to mind as I read Carmen Maria Machado’s 2019 memoir, In the Dream House. Machado, a survivor of psychological abuse, conjures the power and danger of the imagination as few writers can. In the Dream House chronicles her relationship with an abusive girlfriend, winnowing through memories, not only of violence done to her, but of her psyche’s collaboration with the abuser. One potent weapon used against her is the demand that she name her own faults. Another is repeating her words back to her, until she finds herself apologizing for saying them. There are her intimate confessions of past experiences and desires, hurled against her as accusations. But the deepest source of misery is something the abuser has no control over: Machado’s own capacity for love, evident in her precise rendering of what makes her girlfriend marvelous. That is what traps her for so long, as well as what saves her in the end.

Machado’s writing captures the psychological fragmentation that abuse engenders, the crumbling of the self into isolated nodes of thought and suffering. Like a crystal, her memoir grows from a lattice of separate units, each section of text autonomous yet intricately connected to the rest. Some of the book’s passages are rawly autobiographical, some deftly honed with critical insight. In one segment, Machado is a reflective analyst of social forces; in another, a creature bewildered by pain; in yet another, the protagonist in a choose-your-own-adventure that loops claustrophobically back on itself. Even the authorial persona is internally divided, the survivor occupying the first-person position of “I” while the victim takes the second person “you.” At one point, the stronger addresses the weaker, declaring, “I thought you died….” It may be an admission of fear, or of hope.

What does not fragment the author’s identity is her bisexuality. Machado is refreshingly unconflicted about her varied erotic interests. She also calculates the psychic damage of biphobia without casting it as intrinsic to bisexuality itself. The skittishness of lesbians toward dating her has made her feel lucky to have a female partner. Her lack of experience with women leads her to second-guess her own judgment when a relationship turns abusive. Even as alarm bells in her brain alert her, “This is not normal,” she defers to her girlfriend’s claim, “This is what it’s like to date a woman.” Monosexual bias has contributed to putting her at risk.

At the same time, bisexuality offers Machado a key to unlocking the mental prison in which she finds herself. As she notes in the section titled, “Dream House as Fantasy,” discovering same-sex relationships in a heteronormative world can feel like achieving transcendence and leaving the problems of straight society behind. The possibility of domestic violence can become unthinkable under the force of the longing to inhabit utopia, leading observers of abuse, and even its victims, to deny what is happening. Yet bisexuality, by encompassing both same-sex and different-sex relationships, exposes the continuity between them and undermines the myth of pure separation. In Machado’s case, experiencing compassion from an ex-boyfriend helps her recognize her girlfriend’s cruelty and reject it without drawing conclusions about what to expect from all women or all men.

As she ponders the tendency to idealize queer relationships at the expense of acknowledging domestic violence, Machado reflects, “Maybe this will change someday. Maybe, when queerness is so normal and accepted that finding it will feel less like entering paradise and more like the claiming of your own body: imperfect, but yours.” In the Dream House is Machado’s practice of claiming her body, liberating it from abuse and from the mental constructs that have made abuse seem acceptable. Her writing models a path to freedom for others who are similarly trapped, and for all of us who know how easily the mind can become a cage.

Laura Berol lives in Northern Virginia with her husband and three teenage children.