By Martine Mussies (Cyborg Mermaid)

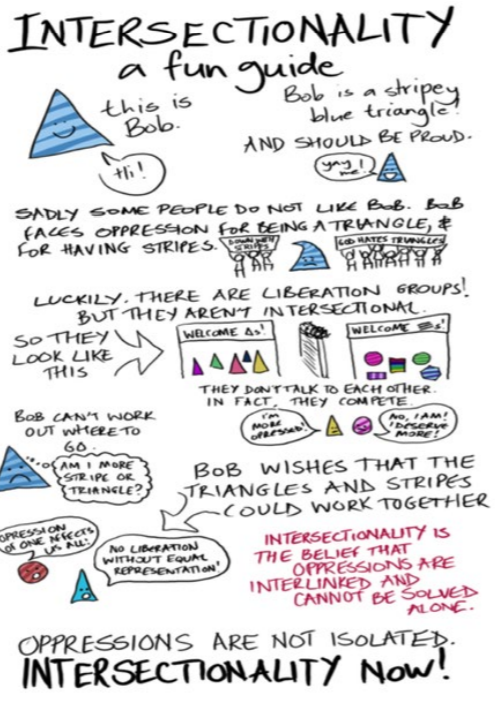

One of my best friends is a true activist and his bathroom is full of posters about socialism, environmental issues, and animal rights. On a printed sheet just above his sink, you’ll find a cartoon featuring Bob, the stripey blue triangle who should be proud—“Yay me!” With this brilliant little infographic, PhD researcher Miriam Dobson explains intersectionality in a heartwarming way. As intersections between forms or systems of oppression, domination, or discrimination are happening all around us, this affects “our group”—bisexual women—as well. Therefore, for this issue of BWQ, I would like to put myself in the shoes of Bob (if he had any…) and tell you about the connections between bisexuality and autism.

This is the first time I am writing about two of the “invisible” aspects of my identity. Why did I not open up earlier? While I agree with Bob that oppressions are interlinked and cannot be solved alone, I also have to admit that speaking up for more than one can be difficult and can cause even more problems. If you request attention for one type of oppression, it can already seem like a lot to ask, and when you also start talking about a second one, it becomes very complicated very quickly and you have to unravel everything to ensure that the prejudices can be nuanced. A beautiful example of such an interpersonal process can be found in “Bisexual women and their relationship(s),” a master’s thesis by Roos Reijbroek (Utrecht University, 2012). In it, Roos describes how one of her respondents reacted to the fact that Roos has both a man and a woman as partners. “[S] he was disappointed and frustrated. [She talked about how I embody the prejudice she often has to counter; that a bisexual would have the need to be with both a man and a woman and not being able to be monogamous.” Thus, for the respondent, the intersectionality between bisexuality and non-monogamy was a problematic feeling that for her own emancipation she even needed to defend herself against the stigmas of the other identity. Stripey triangle Roos made things difficult for her, and I do not wish to make things difficult for autistic women who do not identify as bisexual and vice versa. At the same time, I do not really have a choice, because I often do not know where some of my character traits originate (autism, sexual preference, giftedness, synaesthesia), and there could be mutual influences as well.

Research explains that people on the autism spectrum exhibit difficulty coping with or responding to various social and cultural norms, expectations, and constraints. It should be noted that these social and cultural norms govern nearly all aspects of our lives, including sexuality. Think for example about the research by Gloria Wekker on “mati work” in Afro-Surinamese culture, wherein women bond with both men and women, alongside each other, because they “consider sexual activity as healthy, joyful, and necessary.” As a stripey blue triangle, this seems very valid and logical to me. But when I described these ideas to my classmates in primary school, they bullied me. These social and cultural norms can be quite unforgiving. Owing to the problematic interaction with social norms, people on the autism spectrum often experience unique sexual development. According to recent research findings, the experience of sexuality among autistic persons appears as less hetero-normative (George & Stokes, 2017). Despite the high prevalence of autistic persons identifying as non-straight, there is a dearth of information in research concerning the overlapping of autism and bisexuality, just as there is little public awareness concerning the issue of autism’s interaction with gender identity.

One of the most common explanations for the interaction between autism and bisexuality is the male brain theory of autism. This theory suggests that autistic personalities characterized by extreme inclinations towards masculine traits occur as a result of high testosterone levels in the amniotic fluid. Prenatal exposure to testosterone leads to masculinized future personality and traits (Bejerot & Erikson, 2014). Aside from the male brain theory of autism, the paucity of information concerning bisexuality and autism impedes in-depth awareness and understanding of the subject. Recent research studies show that high rates of asexuality and bisexuality have been identified among people with autism (Gilmour, Schalomon & Smith, 2011). Thus, although the hard link between autism and bisexuality is yet to be established, the chances are that biological and developmental factors—particularly difficulty interacting with social norms and exposure to male sex hormones in utero—play a significant role. Because of the overrepresentation of autistic persons in minority sexual orientations, I would encourage people (for example clinicians, teachers, and caregivers) to be open to different ways of discussing sexuality with autistic persons, as minority sexual orientations present an additional challenge to the stigma and discrimination that autistic persons already face. “My body is like a permanent invisibility cloak from Harry Potter, or invisibility cap if you like classic Greek mythology,” wrote Amalena Cardwell. It is time to remove the cloak, to discuss the “invisible” parts of our identities and be as proud as stripey blue triangle Bob. Yay, me!

Martine Mussies is a PhD candidate at Utrecht University, writing about the Cyborg Mermaid. Martine is also a professional musician. Her other interests include autism, psychology, karate, kendo, King Alfred, and science fiction.