Reviewed by Brianna Lopez

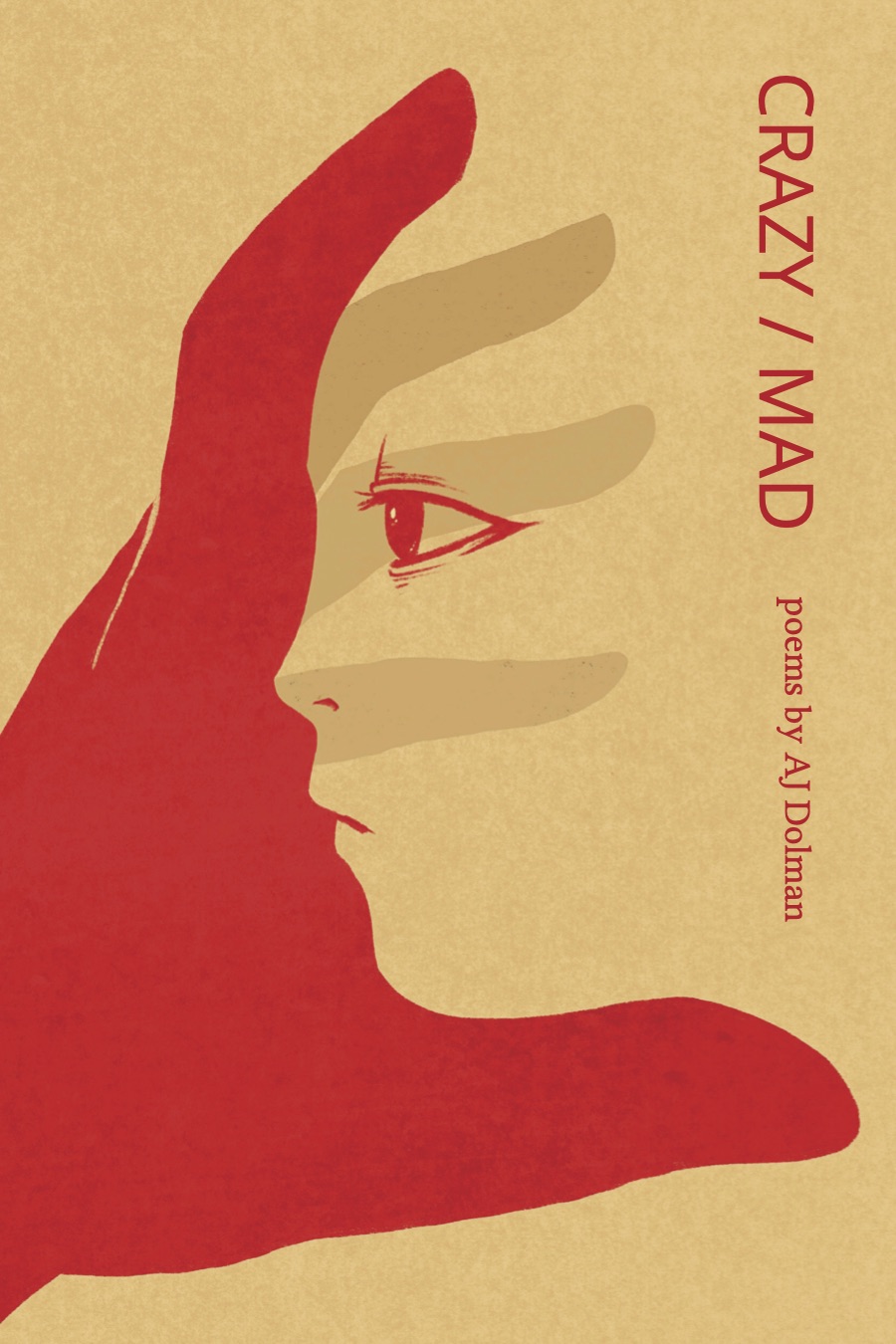

AJ Dolman (she/they) was tired of being voiceless. So they wrote Crazy/Mad (Gordon Hill Press, 2024), a poetry collection about the act of grappling with being silenced—because of mental illness, sexual orientation, and a myriad of ill-composed labels placed on us by a society desperate to categorize us, to determine our worth. Organized into three sections focusing on excitability, stress, and depression, and with each poem title reflecting a symptom one might experience in each of these states, the Ottawa-based writer’s book is arranged in a precise manner. Yet the collection’s lack of punctuation and abrupt end to many of its sentences convey a constant continuation, a desperation to get these words out, a reclaiming of the author’s voice.

The collection is a mere 70 pages of actual poetry, but there is no shortcutting through this reading. Dolman’s diction is explicit, elegant, and poignant. They signal our political climate by writing lines like, “Sunset bleeding orange,” in “Critical race theorist,” a poem that mentions Michael Brown, the Black teenager shot and killed in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014. They use run-on sentences in the poem “Hyperverbal” to mimic the symptom being described, a symptom the whole book is dedicated to. In this collection, Dolman finds her voice, not by telling us what that sounds like, but by forcing the reader to do the work to figure it out. Being playful with formatting and spacing, Dolman’s work requires that the reader pay attention and return back to each poem to reread and gain a deeper understanding of why Dolman made the craft choices she did. Crazy/Mad is a journey toward grasping the complexities of mental health—a journey reflective of the symptoms we endure when faced with mental illness.

When I read the first poem in the collection, “Overthinking” (the only one that exists beyond the confines of the three sections), I was struck by its final lines: “but, boy are we without / language for this shit.” In my annotations, I wrote, The author starts the book by saying this but will prove it wrong, if the book is good. This book is a story of how and why we persevere, a story of resistance, a story of toughness; if Dolman begins the collection without the language to describe the tale she’s telling, she certainly finds that language as she progresses through each section.

The first part of the collection is “Hysteria,” and it is filled with poems that echo this sentiment—the narrator is on a spiral, is manic, is all over the place, and yet somehow we still get a clear idea of what is on their mind. Here, Dolman presents themselves as a strong advocate for womanhood, femininity, and the troubles women face. The line “Husband, know thine enemy,” in the poem “Female rage,” spoke to me, the words a warning—not only from woman to man, but from author to reader. Dolman lets us know that she will be censored no longer.

Depression as a specific plight of women comes up in this section as well. Take “Women’s troubles,” for example, where the author writes, “I forget the deep plummet, / snort blue water in surprise,” signaling the ease with which women can fall into depressive states. They invite the reader to understand the complexities of depression as mental illness by invoking an interpretation of seasonal depression in the story—“I heard of one mother… froze / herself in the creek.” There is a darkness to Dolman’s writing, a need to take a big gulp and swallow, to take a second to breathe. I see this more in what seems to be the narrator’s very clear opinions on childbearing. About the act of growing a baby in one’s womb, the poem “Egomania” bluntly states, “hers was smokier, accented by war, / rage, more childbirth, a torn / canal before cells multiplied / to choke her from inside.” “Perinatal panic disorder” describes children as “a choice you can’t undo” and paints a mother’s guilt: “you hear me dragging us / through rough waters.”

And yet some of the most beautiful lines in the collection sit amid the first section, in “Gynephelia.” The lines read, “her name stills / in my mouth / as it burns.” As a queer woman in a relationship with a woman, this line made me want to call out to my partner, if only to feel the fire that burns between us. It is a timely desire, as the first allusion to queerness comes just pages earlier, in “Egomania,” when Dolman portrays the perseverance required of non-heterosexual people to remain strong in our identities: “My voice…trembles with the wire hum of gendered fragilities, / will never, ever break.” Womanhood, as Dolman tells it, is wrought with deep emotional sensibilities, the foremost one being undeniable strength.

“Neurosis”—the second section in Dolman’s work—invites the reader to find drama in the most mundane of moments, much like we do when we are in a neurotic state. “Self-harm” illuminates the experience of talking to the cashier at your local deli or grocery store while highlighting the age-old adage: “misery loves company.” Dolman assures us that it is okay to find solace in the people who are suffering as much as we are.

Further, in this section, the author tackles a key symptom of neurosis—hypochondria, specifically as it relates to our current political context. “Circumstantial hypochondria” discusses the COVID-19 pandemic, following a group of people who are waiting in line for a COVID test for hours, an experience all too familiar. It includes the following line in its last stanza, “Who is considered expendable hinges on who gets to decide.” This short, curt line speaks to the recasting of our society during the pandemic, the basic premise of the poem going beyond being circumstantial and into a challenging the overall system in which we all are viewed as pawns.

This reality is even harder to grasp for those with mental health issues, as Dolman creates a sense of spiraling that mentally ill people know intimately. This is exemplified in the aptly titled “Slippery slope thinking,” where Dolman ends with the feeling of spiraling in your own mind, of falling, “going all the way down, unsealable” while the rest of the world goes on: “a magpie pecking / at another bird’s nest / outside the sliding door.” With the last line of that poem, the reader is left to sit and spiral on our own, much like most people did throughout the pandemic—a clear innuendo to the fact that art does, in fact, mimic life.

Dolman does one thing particularly right in this collection: writing a last line that can pack a punch. In some poems, the story is clear, and in others, Dolman really makes you work for it, and their last lines are where many of these poems are most understood. It makes sense, then, that her last section, “Melancholia” asks the reader to slow down and sit with the beauty of the sadness she presents to us.

“Despondence” ends with a realization that those suffering from depression cannot get out of their own heads: “You could have been / someone, but if you were, I / probably wouldn’t have noticed.” Another poem in this section, “Dissociation” paints a heartbreakingly gorgeous picture of defeat: “Windspun whorls of crystalized dirt scrape / at my tears until I’m empty, and the ground / here has everything it wanted.” Broken into four sections representing the seasons, this poem roots the reader in nature, de-stigmatizing mental health as something unnatural, forcing us to see it instead as a cycle, as the way things are always going to be. And maybe that should be scary to some people, but not to Dolman. AJ Dolman is a fighter. A resister. The experimental nature of their form and the abruptness of their language makes Crazy/Mad no easy feat for the reader, and that’s because AJ Dolman wants us all to have a taste of what a mental health journey is really like—and she is done sugarcoating it.

Dolman ends their collection by letting the reader down gently. The poem titled “Photo #3: The printer’s case” bears the following final lines: “Here are things you could / have done something with, if something could still have been done.” Perhaps here, Dolman is inviting us to take action. Perhaps these poems are items with which we can still do something, ways to comprehend the intricacies of the issues she is presenting to us. Perhaps something can still be done. Crazy/Mad incites a prayer that this is true.

Brianna Lopez is a nonfiction writer born and raised in New York City in the U.S. She currently works full-time in book publishing and is pursuing an MFA in nonfiction at The New School.