By Ellyn Ruthstrom

For me, women’s space has always meant feminist space; it’s not just having other women around. In fact, some all-female spaces feel incredibly unsafe and uncomfortable to me, such as the mega-hetero-normative ritual spaces like wedding or baby showers or how about a Tupperware party? Not my idea of women’s space. Women’s space to me is about connecting about our strengths and resilience. A place to acknowledge the repression and barriers we’ve experienced due to our identities as women and our other intersecting identities. It is a space that is all about being gender non-conforming because there is no one way to be a woman.

From the time I went to my first Women’s Collective meeting at Heidelberg College in Tiffin, Ohio, back in 1977, I was hooked on women’s space. There I was, a freshman, first year away from home, talking about feminism with classmates, women professors, and members of the administration. We would have deep conversations about the inequalities we all experienced in our varied lives, and I learned so much from those who were older than me who were finally speaking up because they wanted more for themselves and more for younger generations of women.

The Collective brought feminist speakers and performers to campus for the first Women’s Week, including the groundbreaking Sweet Honey in the Rock, an African-American performance ensemble that sang of resistance, women’s strength, and Black history. I also remember hearing an amazing lesbian folk singer/songwriter from Cleveland who taught me that every movement needs its radicals. The radicals have to run out front and cause trouble while proposing things that seem crazy to average people, thus making things slightly less radical appear more reasonable. Every centrist needs a radical to achieve anything at all.

By my senior year, my commitment to building women’s communities was just a part of my everyday life. That year I directed and produced Wendy Wasserstein’s Uncommon Women and Others with a cast of all senior women. The play centers around a group of white women who attend Mount Holyoke together and then reunite five years after graduation. It delves into the varied experiences of young college-educated women during the second wave of feminism, including sex, careers, intellectual challenges, relationship pressures, marriage, and babies.

As a young actor on my campus, I had been frustrated by the choices of the top director who often selected works with very few female roles. My choice of an all-female cast was intentional, and I not only cast other women like myself who had found it hard to get one of the few stage roles, I also cast women who had not acted before. Originally, I was not going to be in the play, but one of the actors had to drop out, and I took on her role, something I cherished.

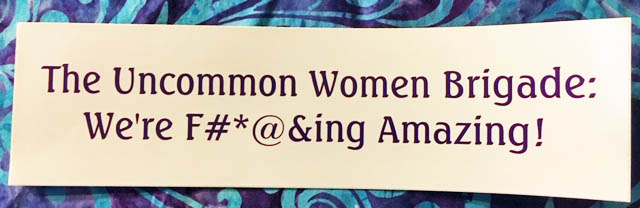

Some of the cast were already close friends of mine, some had been feminist comrades from the Women’s Collective, and some became new friends, but the production bonded us together in a most unique sisterhood for many years. We only performed the play one night on a makeshift stage in the student center dining hall, and we all cried when the packed room gave us a standing ovation. At our 20th class reunion, the whole cast came back together, and we did a dramatic reading of the play on the main stage of the campus that had felt unwelcoming to us decades before. Still to this day, we cheer each other on with one of the play’s recurring lines: “When we’re 40 (or 45 or 50 or…), we’re going to be fucking amazing!” And we are!

Wherever I have lived over my lifetime—D.C., England, Northampton, Boston, Columbus—I have established a women’s space for personal sustenance. When I was living in England with my boyfriend/husband, I sought out a women’s group that was a multi- generational and multi-cultural feminist space that connected me to the women who were demonstrating at Greenham Common in the south of England against the presence of U.S. cruise missiles. Talk about women’s space! These anti-nuke activists created women’s encampments outside the U.S. base in protest and intersected their anti-war message with an anti-patriarchal one. Women maintained camps at Greenham from 1981 until 1987, and this woman-centered activism inspired many other women’s actions throughout England, Europe, and beyond.

Moving to Boston with my husband, I ended up working for a quarterly feminist spirituality and politics magazine, Woman of Power. During that time, led by the incredible Starhawk, I danced the spiral dance with a roomful of women yearning for a connection to goddess energy. I was also part of a reproductive rights group in Cambridge that included women of all sexual orientations, and I volunteered at Sojourner magazine, a national feminist monthly. I was a part of all of these spaces as a straight woman, ostensibly.

I didn’t come out as bisexual until I parted ways with my husband, and once I was out, my need was not just for women’s space, but for queer women’s space. And, more specifically, bisexual women’s space. One of the first things I did when I moved back to Boston in 1994 was to visit the Women’s Center in Cambridge to look for a place to live, to find a job, and find bi women. I found the Bi Women’s Rap Group, a weekly, peerled, two-hour meeting that centered around a different theme or question each time. Often, every seat would be full, and people would be sitting on the floor, 15-20 bi women soaking up a safe space, talking to each other about issues they’d never spoken to anyone about. I met women in that room who are still close friends to this day. And from there I joined the Boston Bisexual Women’s Network (BBWN), which is still my community touchstone after 25 years.

The concept of women’s space has never been uncomplicated, and my nostalgic retelling hasn’t yet included any of those ripples. What about spaces that women of color didn’t feel welcomed into? What about the spaces where middle-class women didn’t open themselves to working-class or poor women? What about when cisgender women didn’t want to include transgender women in their spaces? What about when lesbians didn’t want to include bisexual women? Or when straight women didn’t feel comfortable with queer women?

All of those things have happened within spaces that I participated in or heard about. And though some of these clashes were absolutely wrenching experiences to live through, those reckonings are so important for movements to come to terms with in order to grow, become more inclusive, and to deepen the connections between women of differing identities and experiences. Feminist communities are not the only ones that have been pushed to do this, but in some ways, they are more likely to lay bare these conflicts.

Queer women’s space constantly goes through these growing pains and so does the larger feminist movement. But I’d rather be a part of a community that wrestles with these complexities instead of trying to ignore them. I am also not naïve enough to believe all feminists hold the same values of inclusivity that I do or even have the same understanding of what feminism is. Despite all its faults, I still turn to women’s space, to feminist space, still believing that there is no one way to be a woman.

Ellyn Ruthstrom is not letting the bastards grind her down, even when it seems like we’re surrounded by them. She feels so lucky to be a part of the vibrant bi+ community of Boston.