Reviewed by Sarah E. Rowley

For decades, the American publishing industry has been notoriously hostile to lesbian and bisexual women writing fiction about lesbian and bisexual characters, in a striking contrast to its treatment of gay male authors. Despite more than a decade of public conversation, most high-profile novels by and about queer women published in the US still come from the UK or Canada, from the pens of white authors Jeanette Winterson, Sarah Waters, Emma Donoghue, Helen Humphreys, and the like.

The one exception has been Young Adult (YA) literature, which has experienced a great boon since the Harry Potter books proved not only that adults would openly read it, but also that it could immensely profit publishers. Simultaneous with the general rise of YA’s profile has been growing concern with queer youth, leading to an explosion of novels about LGBT teens. While boys’ stories still outnumber girls’ and the very occasional trans teen tale, the YA aisle has become one of the best places to find LGBT fiction.

But these LGBT novels, like YA lit in general, have remained overpoweringly white. I know of only two YA novels about queer African-American girls—Rosa Guy’s Ruby, probably the only black nationalist lesbian YA novel, and Jacqueline Woodson’s slender but poetic The House You Pass on the Way. Ruby, published in 1976, has all of its era’s negative stereotypes about same-sex relationships (including a suicide attempt and the idea that the heroine can be romantically redeemed by a man), but remains fascinating for its politics and portrayal of 1970s New York City. The House You Pass on the Way, from African-American YA powerhouse Woodson, has a quietly affecting story and achingly beautiful writing, but ends abruptly after only 90 pages.

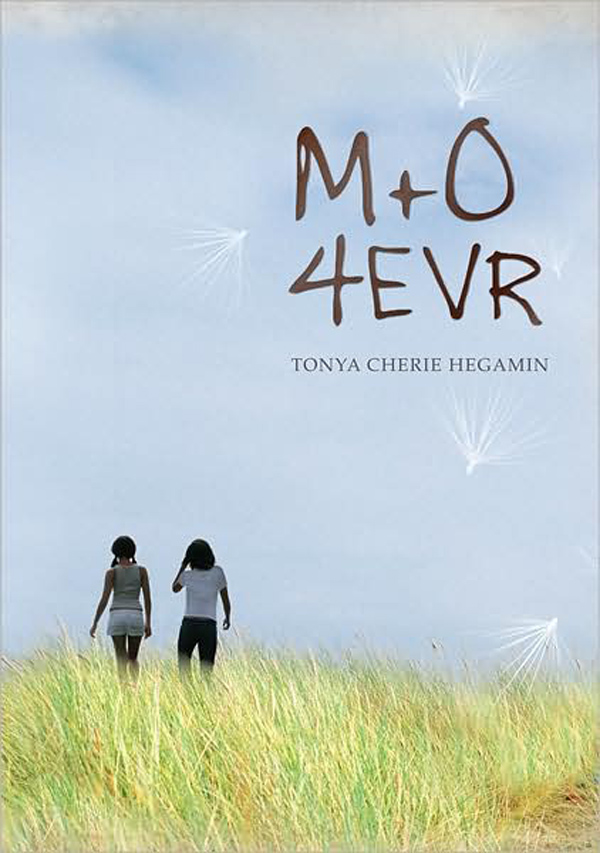

In this context, it’s a real pleasure to discover a third novel about a queer African-American girl, especially one as moving and skillfully written as Tonya Cherie Hegamin’s M+O4EVR.

M+O4EVR shares a number of similarities with The House You Pass on the Way. Both novels are concerned with rural African-Americans—another under-represented group—and family legacies (the protagonist of The House You Pass on the Way suffers more socially in her black town from being the granddaughter of two Civil Rights martyrs than she does from her crush on another girl). They share, too, the distinction of being uncommonly well-written, every word as precisely chosen as poetry.

But M+O4EVR stands on its own. Its heroine and narrator, Opal or O, has been in love with her best friend, Marianne or M, all her life. The daughter of loving but absent parents, O has been raised by her grandmother, Gran, who has also embraced Marianne, a biracial girl living with her troubled white relatives. Together the girls have rambled (“my brown hand in her yellow one”) through the fields and woods of their rural Pennsylvania town, pretending to be the African goddesses Mlapo and Omali and trying to catch sight of Hannah, the ghost of an escaped slave who haunts a nearby ravine.

But in high school Marianne has tried to find popularity by ditching the tomboyish O, who has clearly built her life around M, sacrificing her own dreams at the altar of her love for her self-destructing friend. When Marianne breezes back into her life the day after becoming the town’s first black homecoming queen, O, drowning in her unrequited passion, can’t help but follow along.

Hegamin drops us into the middle of the girls’ complicated relationship and lets the layers of personal and family history unfold slowly, one by one. From the moment the vivacious but insecure Marianne burst onto the page we the readers know she’s headed for trouble, but we’re as shocked as Opal when she dies unexpectedly, in the same ravine Hanah did, at the end of chapter two.

The rest of the book traces O’s struggle to grieve, make sense of Marianne’s demons, and regain a sense of who she is without her beloved obsession. In this she has the help of her family, particularly her Gran, who tells her, “Black folks got enough ghosts in this country to be haunted until the end of time. Why you want to haunt yourself with the one ghost that’s trying to leave you in peace?”

Another ghost, that of Hannah the escaped slave, also appears in the novel, and O & M’s story is interwoven with hers, a tale that Gran has told so many times Opal knows it by heart. In it Hannah finds passion and a new beginning with a black Nanticoke man, and her sections of the book echo the themes of love and the need for freedom.

While the ghost story pales beside the more vivid present-day action, it does provide a sense of history and community, which is perhaps exactly what Opal needs. It’s strongly implied that Marianne’s tragedy comes in large part from the harrassment she has received from whites for not fitting neat racial categories, and her family’s inability to provide protection and a sense of history. Opal, in coming to understand why M could not accept her love, find her own new beginning.

Though sad in places, M+O4EVR is deeply moving. While Hegamin makes you feel the ugliness of racism in M & O’s world—for example, in O’s abiding disgust for Walmart, the giant chain store where a pair of white girls taunted M as a child—she’s equally gifted at communicating love, as in the scene in which O’s quiet father uses a story about constellations to tell her a truth she doesn’t know she needs to hear. I’m afraid that readers will be scared off by the death in this book and miss out on a lovely reading experience.

All of the characters, from the wild Marianne to the self-effacing O to all their associated relatives are vividly drawn. And Tonya Cherie Hegamin’s language—clear, precise, and beautiful without ever distracting from the primacy of the story—is a pleasure to read. This is her first novel. I certainly hope it won’t be her last.

Sarah is (with Robyn Ochs) editor of Getting Bi: Voices of Bisexuals Around the World and current board chair of The Network/La Red, which works to end abuse in lesbian, bisexual women’s, and transgender communities.