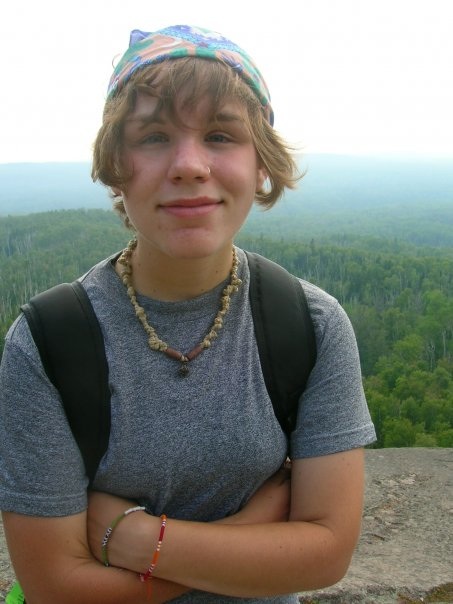

By Willa Simmet

I don’t know what happened in the womb. Two eggs lying next to each other in mom’s strawberry-jam-like ovaries are shot with two meteorites of sperm. One egg receives the first shot and gets to pick whether to grow a penis or a vagina. The next egg picks. And my twin and I begin our trek into society, according to the gender given to us. Eight months later, two bodies pour out of the red womb and onto a white sheet.

First things first: “It’s a girl!” For the next baby: “It’s a boy!”

Rubber hands, white like the sheet and everyone’s skin becomes splatter-painted with our blood. Only a few seconds are allotted to us, before a color gums onto our skin. The person who I will come to call Dad holds me, the baby in the pink blanket in his arms and mom grasps onto my twin wrapped in his blue blanket.

The white bathtub is the womb. We kick through the suds with our four-year-old feet, pretending that we are still unborn babies. We crawl from one end of the womb to the other. Mom picks us up and out of the womb. She helps my twin put on a red flannel shirt and blue sweat pants. I scream as she pulls a denim dress over my head.

My twin and I play our toy drums outside. He slips his Snoopy super performance tee shirt off of his head. I reach my arms through the top of mine, but Mom slips it back onto my head.

“Little girls can’t take off their shirts,” she says.

Angry, I chuck my twin’s toy drumstick into the puddle.

Ten years old, I go with my family to Walmart. Walking up and down the aisles, we throw items into the cart. My twin and I fight for bags of Kit Kats and rubber super balls to add to our collection. Mom puts a blue package in the cart. She often buys these packages that look like packs of diapers. Ten years old, I go with my family to Walmart. Walking up and down the aisles, we throw items into the cart. My twin and I fight for bags of Kit Kats and rubber super balls to add to our collection. Mom puts a blue package in the cart. She often buys these packages that look like packs of diapers.

“What are these?” I say, as the check-out clerk slides the blue diapers over the scanner.

Mom doesn’t tell me. “Let’s take a walk when we get home,” she says.

We start on the same path that we always take, the milelong path past the 100-year old houses with rotting couches and Budweiser cans on their front porches.

“A young girl becomes a woman when she starts menstruating. This means that she bleeds out of her vagina once a month and those things in the blue packages are there to soak up the blood,” Mom says.

I start crying.

“I don’t want to!” I sob. “It’s all your fault. I don’t want to!”

I take a shower and Mom sees her daughter’s naked body. She says that she wants me to wear a bra. I cry again. My twin doesn’t have to wear a bra. The next day she comes home with a plastic grocery bag of three white bras. She keeps it a secret and tells me to follow her upstairs so that I can try them on.

I am 11 years old. I hold my arms above my head to do a dive into the deep end. My twin and his friends laugh when they see my underarm hair, soft like a baby’s, and coarse like tree bark. They still haven’t had a voice change or a fresh supply of fuzz. I hide underwater. I pop up and swim toward the side of the pool, keeping my upper arms hugged to my chest.

As a 12-year-old, I hold my breath before I pee. During a walk, I had decided that if I held my breath before I peed, the blood wouldn’t fall. I pray now too, sure that if I pray God will not condemn me to this place.

While at basketball practice, I sit alongside the other fifth graders with my back against the wall. We stick our legs out in front of us, and I see that I am the only girl with hair plastered to them. My teammates run their hands over their legs, smooth like the outside of my twin and my super balls. I go home and take a pink plastic razor from the top shelf of the cupboard next to the toilet and scrape the hair off of my legs.

It happens today. While sitting on the go-kart seat with Ben, we swing past fake palm trees and back around toward treasure chests on a pirate ship. Something’s wet. I had not held my breath or prayed. We hit one of the rubber tires. It feels warm and it’s still wet. Ben gets out and tries to maneuver the car to the right so we can continue with the race.

“Get out! Get out, Willa!”

I sit there, silently. I do not want to move.

“Get out! Get out!”

He wants to win. My pants are white. I sit there. He shakes my arm and pulls me out. I inch along the fence toward a café. I inch along the white wall toward the bathroom and slump onto the toilet, where I peer inside of my pants. A red tundra greets me. I didn’t ask for this. I wad up some toilet paper, for the first time, and put it onto the Spongebob thong. Some of it wads up inside of me as I sit down. I perch on the bench, tell Ben that I am sick, call my parents and go home.

I don’t tell Mom about the tundra. I don’t tell anyone. I go upstairs and reach inside the blue package for the first time, pull slowly at the perforated edges on the outside of one of the pads. I don’t want to make a sound. My twin is downstairs playing the piano, singing in a voice that has not changed. I have the thing open. I unpeel it and plaster it on top of the tundra. I place the orange wrapper at the very bottom of the garbage pile, digging past used Kleenex and Dixie cups. I flush the toilet, wash my hands twice, creak open the door, scurry to my bedroom and hide myself under the white comforter.

Fourteen years old and the blood pours out of me in buckets. Before school I plaster two pads on top of each other. We have no lockers at school, so there is no place to hide the pads during class. In the bathroom, I do not want to make a noise. Toward the end of the day, it feels very wet. I wrap a sweatshirt around my waist. The red tundra has crusted to the butt of my pants. I turn my head to see a boy pointing at my ass, laughing. I decide not to come back to school. For a week and a half, I am sick.

I try again and again to push a tampon inside of me. I want to plug myself up. I sit on the toilet with a cardboard box filled with wads of cotton between my feet. My parents are at work. My twin is playing video games. This is a good time to practice. I think I have one inside of me. I waddle around. I waddle back to toilet, reach my hands inside and yank it out. I repeat. I repeat again. I put the mess inside a plastic bag, and take it outside to the garbage can. If I sit the right way on the couch, I can’t feel it.

I go to the ninth grade dance. I struggle with slapping make-up on my face. I struggle with buying the boy a corsage. I struggle with wearing high heel shoes. I struggle with rubbing the back of my body against the front of his.

I struggle. I go to the girls’ bathroom and sit.

I shave my head. Dad and I stand on the floor, in the audience at the Neil Young concert. I wear my Dad’s shirt from the 1974 concert that he had attended. Stale cigarette smoke funnels into my ears. The man talks, “Hey, I was at that concert, man, back when Neil was a young dude.”

“This is my Dad’s shirt. He was there too.”

“Dude, your son’s got a sweet shirt on,” he says to my dad.

My Dad’s face is red now. I walk through the back of the crowd to the girl’s bathroom, pushing my chest forward as I walk in.

I grow my hair long again.

Grandma says, “You look like such a nice lady.”

I thank her. Three days later, I give Anna the electric razor. “Mohawk,” I say.

James and I go to a concert. Roo Roo Kangaroo asks for all the ladies to come to the middle. Roo Roo Kangaroo asks for all the guys to come to the middle. I don’t move.

Willa is a student at St. Olaf College in Northfield, Minnesota, where she studies English and Spanish.