By Tanya Anne Bassie Bowers

My first day of college, I proudly wore a black t-shirt with colorful Andy Warhol-like images of Madonna silkscreened on the front and her full name, “Madonna Louise Veronica Ciccone,” on the back. To anyone who commented on my favorite celebrity, I declared, “If Madonna were interracial, she’d be me.” In addition to our both having been given two middle names, I tried to project the same spunk, the same charisma that the singer/dancer/actress did. No one could tell her who or what to be. She was an influencer before that was a thing.

I hadn’t always felt so inspired by her. One weekend in sixth grade, the MTV VJ Martha Stewart shared that the 23-year-old singer, Madonna, hailed from Michigan. In the Burning Up music video, a bleached blonde heavy on the brown roots rolled around an asphalt street. The visual story cut to different images—a closed door with many locks, multiple eyes, and a mouth with hot pink lipstick. The nominally pretty woman jumped and spun around in black and white clothes. The song was OK, but I wasn’t particularly impressed.

After the Borderline video premiered, White girls started affixing bowtie clips to their sprayed hair, wearing rubber gummy bracelets around their wrists, and layering fluorescent with netted shirts. I thought that style was cheap.

Over that 1983-1984 school year, I transitioned from my preppy style with my wavy shoulder-length side-parted hair to zippered Guess denim cigarette jeans held up by a navy spiked leather belt. I matched it with a two-toned gray-blue denim vest.

Beyond that, Madonna’s raw sexual energy went against what I had been told about getting ahead with my mind, not my body. My feminist politics aligned more with Cyndi Lauper’s videos of girl-positive empowerment.

I’d “gone” with a boy for the first time at sleep-away camp the summer before. We hadn’t kissed, but being asked and having the status gave me bragging rights.

The next year during sleepovers with my best friend, we feigned innocence as our hands “accidentally” brushed against each other’s privates over our nightgowns.

After Madonna’s controversial MTV Video Music Awards performance and her Like a Virgin video premiered, I called her a “slut.” My father used the term to describe women who flaunted their sex appeal.

I adopted my mother’s classic, masculine style, inspired by Diane Keaton: the oversized blazer, tailored slacks, and button-down shirts. With my long feet, I often borrowed her size nine and a half beige suede Oxford loafers. I brushed my dark brown hair which had just changed textures with puberty into a frizz.

Nonetheless, my cassette tape collection included all of Madonna’s albums.

I couldn’t understand why the artist sang about keeping an unexpected pregnancy in the Papa Don’t Preach video. It seemed counter-intuitive.

In 1987 Connie Chung interviewed me for a TV special called “Scared Sexless.” My long dark hair had been diffused into curls. I attested to being a virgin (a word that came into my vocabulary thanks to the artist herself), given my fear of contracting HIV or getting pregnant.

A female friend and I formed an intense connection. We professed our affection for one another in written exchanges and drew hearts and flowers on the edges of every sheet. I wasn’t physically attracted to her. Reading her letters filled me with immense joy, and I longed to find them in the mail. The next school year she pulled away. It seemed like the closeness had scared her.

Madonna’s Express Yourself video was a game-changer. When her nakedness wasn’t hidden behind satin sheets, the gender-bending icon was dressed in slinky, skin-hugging dresses or a pin-striped suit…albeit with a bra underneath. She grabbed her crotch defiantly as men did.

Paparazzi captured her with Sandra Bernhard. Were they involved romantically? Although Madonna had always had gay male admirers, now her sexual orientation (which was called sexuality then) was up for speculation.

If Madonna was man enough to own her same-sex desires, I could be too. In my senior year of high school, I confessed to my therapist that I feared I was gay. The psychologist wrote off my preschool oral/manual genital explorations and elementary school fondling with girls as experimentation; still, in the pit of my stomach, I sensed she was wrong. That summer I came out in front of other teenagers at a social justice training.

Now a thick, black belt held up my oversized denim blue jeans. I pulled them down a couple of inches, so they sagged. I tucked one of my father’s white V-neck undershirts under a rectangular, metal belt buckle. I wanted to have the same power…that same privilege boys possessed. Mind you, I interspersed these clothes with short, fashionable baby-doll dresses. I sported hoop earrings no matter my attire.

As I vogued at clubs, I wore trousers with a black sports-bra-like top that emphasized my cleavage. Revlon’s Blackberry lipstick colored my lips. I filled in my already thick eyebrows with black eye pencil. At my university’s Gay-Lesbian-Bisexual Association parties, I tore off my shirt to move to the beat in just a bra. I wrapped my long hair into a knot behind my head as I sweat.

Then Madonna’s Justify My Love videos opened the floodgates. I was open to men and also to women, and I danced close with both.

Once the Erotica video aired, I had come into my own around my sexuality. No longer did I need Madonna to feel comfortable with my attraction to women. I knew I was bisexual, and she helped me be unapologetic about it. While I was still male-leaning, I also dated women.

No one was going to tell me with whom to have relationships based on gender or race, but the latter is another chapter.

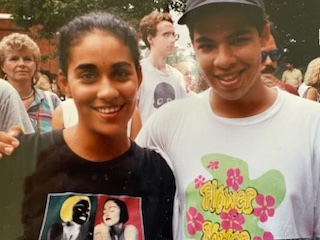

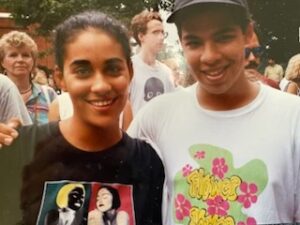

Tanya in 1990, with a friend

Tanya Anne Bassie Bowers (she, her) lives in eastern Washington, U.S., with her husband and their son. She attended Wesleyan University as an undergraduate and Antioch University Los Angeles for graduate school. Subscribe to her substack: https://substack.com/@tanyabowers.