By Julene Tripp Weaver

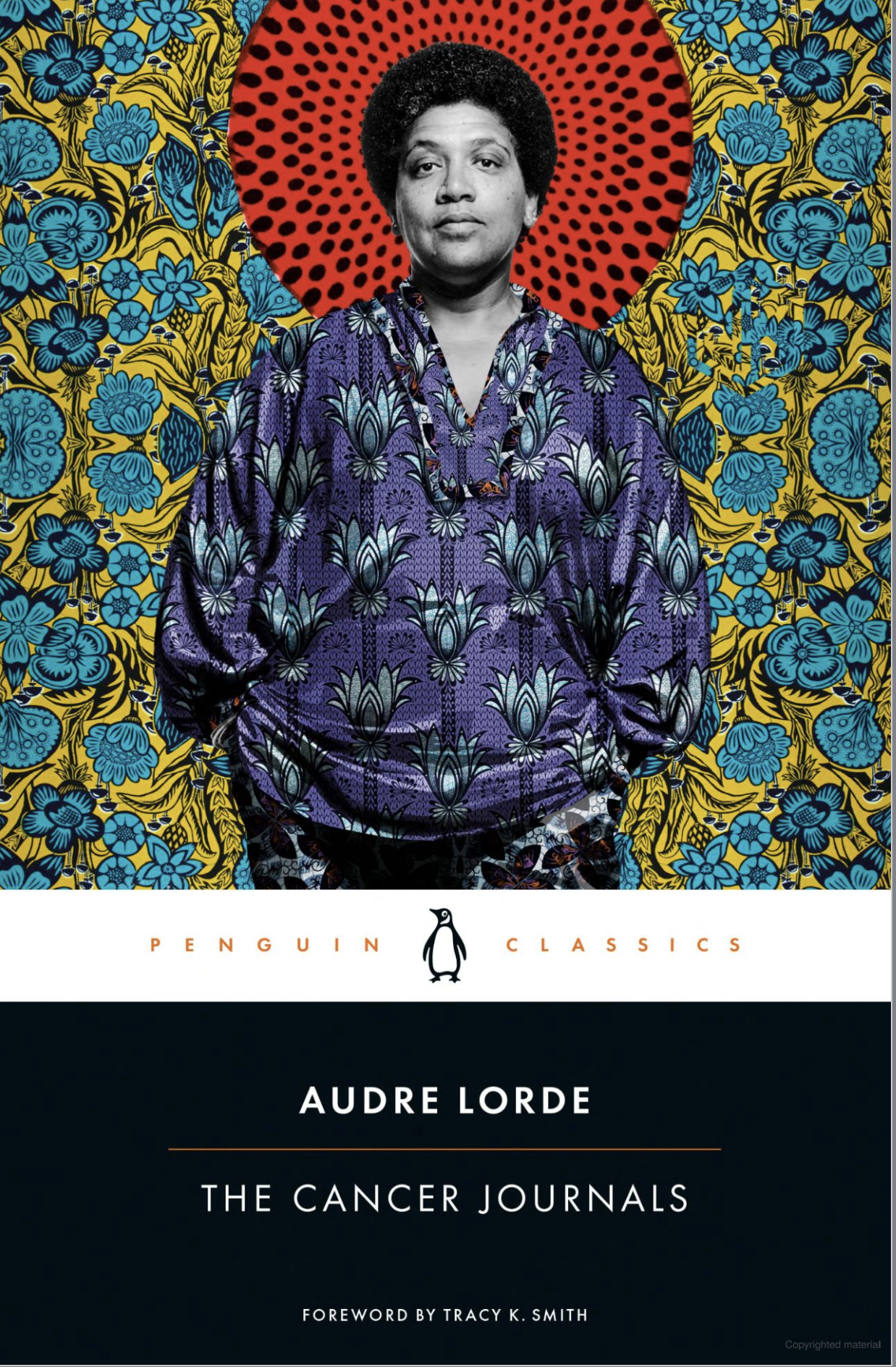

It took years of therapy before I enrolled for an undergraduate degree. I had taken courses at night at a community college to figure out my next step. After I moved to Manhattan, living on East 76th Street, in a tenement building with low rent, I was ready to pursue my long-buried goal of writing. After my father died, when I was 12, I started writing to cope with my grief. By 1982, I was ready to face my fears and study with one of the most powerful poets, Audre Lorde. A lesbian feminist icon who wrote the book Cancer Journals. After her breast was removed, she refused to wear a prosthesis. She taught poetry at Hunter College one semester each year. Living in Manhattan, I was taking writing classes at the YMCA, had joined the Feminist Writers Guild, and was in a critique group. I knew I had to study with Audre.

In her classes, we read our poems out loud and critiqued each other’s work. In Poetry I, she handed out a Xerox of the e.e. cummings poem, “anyone lived in a pretty how town.” Passing it around, each of us read a line out loud, then we discussed the poem. How it surprised us, the impact we felt, what the author was doing to craft the poem. Without a background in poetry, it was my introduction to e.e. cummings. I adored his quizzical, off-centered language. Other than a classic poem Audre brought in on occasion, there was no formal study of any of the usual canonical poets.

Audre Lorde spoke and I listened, taking notes, even though she preferred we simply listened. If tired, I woke up in her presence. I wanted to absorb everything she said. After any of us read a poem, her first question was: “What do you feel?” Five semesters I sat in a circle with her in a small group, typically under 10 students. Mostly women with an occasional man, and many of us took every class Audre taught. My biggest lesson was from her insistence that a poem’s purpose was to make the reader feel.

One of my early poems did not please Audre, she walked over to me and asked me how old I was. I answered 32. “Thirty-two!” She huffed, “You know more than this!” She threw the poem at me. My face turned bright red. Her huge “HUH!!!” written across the page. My poem about foot binding left her cold. When I told a friend my horror at Audre’s response, she said, “Well, you’ll have to write a poem she likes.” It helped to be supported by a calm friend who was in a Ph.D. program. Her simple statement helped ease my anxiety. She was right, I had to buckle down and write from what I knew.

Another long narrative poem I wrote about my experience in a sweat lodge did not interest her. She said, “A poem is not a story.”

On Tuesday October 25, 1983, Audre entered the classroom like a storm, asking, “Do you know what happened today?” She threw her huge handbag filled with books onto the desk. We sat in silence. “Today is not class as usual. The United States is invading my home country, Granada. My family and friends are at risk!” She gave a long impassioned speech about the history of U.S. imperialism. I began to understand how our country manipulated other countries.

Meeting with her one-on-one was awkward because I never wanted our meetings to end. She asked, “What do you want?” She saw the longing in my eyes. I didn’t know what to say. My subconscious wanted a connection I never had with my mentally ill mother. She suggested, “Go jogging; do anything to get yourself moving.” Studying with her was what I was doing. I needed so much from her. She hugged me that day. Enclosed in her arms, I felt loved. Something I didn’t feel from my mother. Her nervous system calmed me, I didn’t want to let go. After I graduated, I found Continuum Movement work as a way to work with my body.

Audre would tell us we had to carry on the work, that she would not be here forever. How could any of us live up to Audre’s work in the world? A few poets from our groups continued her work; Donna Masini has published and now teaches at Hunter; Melinda Goodman works with the Audre Lorde Center. I’ve published four books. What she did for human rights, gay rights, women’s rights, and outsiders in every realm was huge. I still ask myself how I can live up to her stamp on our wide world. After moving to Seattle, WA, I achieved a master’s in counseling and became involved in the AIDS movement, working for 21 years in AIDS services.

Hunter should have been honored to have Audre as a professor. We didn’t know she still had cancer. She didn’t talk about it in class. I remember her telling us she asked for health insurance coverage for the semesters she didn’t teach. The dean of Hunter, a woman who later became an official in the federal government, told her she was “lucky to have a job as a poet,” and refused her request. Audre was already a world leader for human rights; she set up an organization in St. Croix for women in abusive relationships; traveled to speak at conferences worldwide. She spoke in Australia and was known as “Sister Outsider”; a book of her talks was published with that title. She had a degree in library sciences from Columbia; she deserved health benefits. Audre shared that she had worked in a factory painting radioactive radium onto clock dials and how all the workers, young women like herself, used their bare fingers. When she died, her body was riddled with cancer.

Audre used her writing and voice to change the world—and she wanted us to step up. Working with her in class, I never felt up to her standards, but I learned many skills from my moments of mortification. One time, incensed that my lesbian Black lover didn’t vote, I wrote a poem about it. Audre expressed anger at the tone, the blame, and the racism in my poem. “This is not the way you change people,” she said. She asked the others in the group what they felt in my poem, and they too felt anger. I had a lot to learn.

There were many embarrassing moments with Audre. She didn’t hesitate to say what was on her mind, which I admired. I wanted her honesty. The basic learnings for writing poetry came through critique. Why the gerund? Why did you use a suffix “ly”? We didn’t study form or the classics but were encouraged to go to readings and to keep a journal of each one. Our work was to engage with poetry in the real world. June Jordan’s reading in an off-off-Broadway theater had me sobbing. Why weren’t women poets like Audre and June running the world? Audre recommended I read Wanda Coleman and Faye Kicknosway, two poets whose work she believed resonated with mine. Reading their work, I felt Audre’s awareness of the strengths of my poetry. My final project for one of the classes was an interview and report. I chose to interview Kicknosway, who used drawing with her poetry. I felt seen and heard by Audre in her recommendations.

Despite my fear, I studied with Audre every semester she taught. I wrote and re-worked poems, and I organized a poetry manuscript by the end of my fourth year. A few poems were published in the school’s two journals, The Olive Tree Review and the Returning Student Newsletter. At graduation, my poetry won the Honorary Mary M. Fay Award in Poetry. After graduation I gave a reading at La Mama, an experimental theater in the East Village. Long after I graduated, Audre came to me in a rare dream and hugged me. In every poem I write, I revisit her questions. Her mentorship from those early years continues to be a guiding light.

Julene Tripp Weaver is a writer and psychotherapist in Seattle, Washington, U.S. Her fourth collection, Slow Now With Clear Skies (MoonPath Press, 2024) previewed in June; her last book, truth be bold: Serenading Life & Death in the Age of AIDS (Finishing Line Press, 2017) won the Bisexual Book Award, four Human Relations Indie Book Awards, and was a finalist for the Lambda Literary Awards. Her work is widely published and anthologized. She was a Jack Straw Writing Fellow (2023) and is a Through Positive Eyes “Artivist.”