With this issue, we re-introduce this column, under the capable supervision of Renate Baumgartner and Soudeh Rad. Renate Baumgartner is currently researching on bisexual women and their experiences of discrimination in Vienna, Austria. She holds a PhD in natural sciences, is a bi+ activist, and offers workshops for bisexual empowerment. Soudeh Rad is an Iranian gender equality activist based in France and cofounder of Dojensgara.org, a website about bisexuality in Persian. Some columns will be written by Renate, some by Soudeh – and some by both. If there is research on bisexuality that you would like them to be aware of, please write to them c/o biwomeneditor@gmail.com.

Bisexual women and Trauma: Findings from “The National Intimate Partner & Sexual Violence Survey”

By Renate Baumgartner

Sexual violence against women is recognized as an enormous social problem. A large body of research exists on this topic. Research about sexual violence against LGB (lesbian, gay and bisexual) people is also available. However, most studies investigating the experiences of sexual violence by lesbian and bisexual women pool the data into “sexual minority women” (Rothman and Baughman 2011). Thus, data explicitly focusing on bisexuals or comparing their experiences with heterosexual or lesbian women is scarce. In 2013 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provided the first nationally representative data on the prevalence of sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence in the LGB population (Walters, Chen, and Breiding 2013). The report is admittedly quite shocking for any woman who identifies as bisexual. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS) is an ongoing, nationally representative survey. Data collection for the report issued in 2013 took place in 2010. Participants had to be over 18 years old and had to speak English or Spanish. People across the United States were chosen randomly and phoned over landlines and cell phones to gather responses to the survey questions. In total, over 16,500 people took part: 9,100 women and 7,400 men. During the interview people were also asked: “Do you consider yourself to be heterosexual or straight, gay or lesbian, or bisexual?” Of the women, 2.2% of the women identified themselves as bisexual, 1.2% as lesbian, and 96.5% as heterosexual.

The goal of this survey was to learn more about the prevalence of experiences of intimate partner violence, sexual violence, and stalking victimization among adult women and men in the United States. The survey included questions around lifetime victimization as well as victimization in the past 12 months.

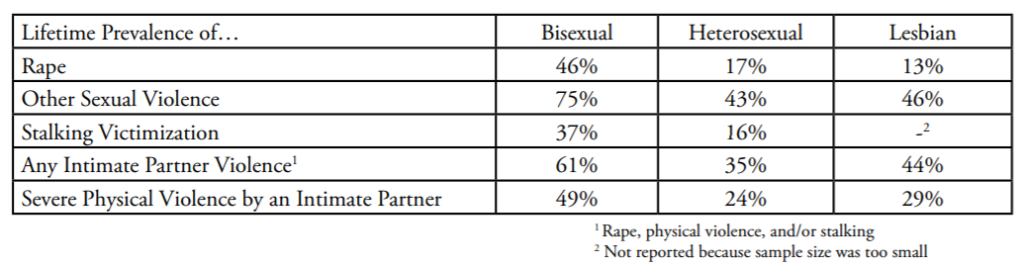

The report concludes: “bisexual women had significantly higher prevalence of virtually all types of sexual violence and intimate partner violence…when compared to both heterosexual and lesbian women.” Put into numbers, this means that nearly half of bisexual women had experienced rape at some point in their lifetime. That is compared to one in eight lesbian women and one in six heterosexual women. Most bisexual women had been between 11 and 24 years old during their first experience of rape. Seven out of 10 bisexual women had experienced other forms of sexual violence such as unwanted sexual contacts or being pressured in a non-physical way for sexual contacts, compared to almost half of the heterosexual and lesbian. One in three bisexual women had experienced stalking, compared to one in six heterosexual women (data of lesbian women was not reported). The survey differentiated between intimate partner violence and violence by perpetrators who were strangers or acquaintances. Six bisexual women out of 10 had experienced intimate partner violence, compared to three or four out of 10 for heterosexual or lesbian women, respectively. Half of bisexual women had experienced severe physical violence by an intimate partner, as have one in three lesbian women and one in four heterosexual women. Physiological aggressions from intimate partners were even more common: more than seven out of 10 bisexual women, six out of 10 lesbians and half of the heterosexual women reported this experience.

The report suggests the following actions:

- More research is needed to identify potential risk or protective factors for rape in adolescent LGBs.

- Training for service providers who respond to intimate partner and sexual violence should be enhanced.

- State and local criminal justice systems should consider how their services for survivors of sexual violence serve people regardless of sexual orientation.

- Unbiased training and expanded education are needed for service providers who focus on LGB issues.

The report is precise and streamlined. However, many questions remain unanswered. For example: were the women out at the time of the sexual assault or at all? Also, no hypothesis is offered why bisexual women experience sexual violence to such a high degree. I would hypothesize that society and perpetrators look at bisexual women differently from other women. Antibisexual prejudices like hypersexualization or the attribution of promiscuity could be reasons bisexual women are targeted.

In summary, this report offers the first US national-level data on the prevalence of intimate partner violence, sexual violence, and stalking among the LGB population. It is a revealing piece of research. In addition to providing scientific validation of the importance of caring for the health and well-being of bisexual women, the study also offers valuable information for bisexual organizations and activists.

Bibliography:

Rothman, E. F., Exner, D., & Baughman, A. L. (2011). The prevalence of sexual assault against people who identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual in the United States: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 12(2), 55–66. doi.org/10.1177/1524838010390707

Walters, M.L., Chen, J., & Breiding, M.J. (2013). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 findings on victimization by sexual orientation. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nisvs_sofindings.pdf