By Nicola Koper and Robyn Ochs

Following along with this issue’s theme, here is a brief summation of the recent history of bi+ identification and research in the United States:

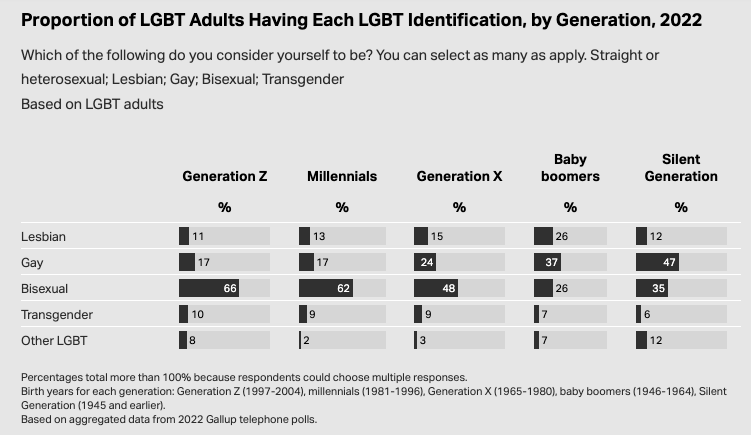

Gallup’s 2022 poll question on LGBT identity shows increases over the past decade in the number of people and proportion of all LGBT folks who identify as bisexual1. Now, well over half (58%) of LGBT people in the USA identify as “bisexual.” This increase in bi identities over time is even more clear when we compare younger and older generations: a full two-thirds of LGBT Gen Z folks (born 1997-2004) identify as bi, while only a quarter of LGBT Baby Boomers (born 1946-1964) do.

What has led to this blossoming of bi (and bi+) self-identity? One important reason has been our increasing familiarity with these words. The term bisexual has changed substantially in recent decades in its cultural use and meaning. Kinsey noted as early as 1948 that sexualities are not binaries but instead are continuous. However, this concept was not adopted widely for many decades. In “The evolution of the word ‘bisexual’ — and why it’s still misunderstood” (nbcnews.com), Alex Berg interviewed several people who identify as bi, but recall that word being rarely used prior to the 1980s. Most recently, in 2020, the Merriam-Webster Dictionary expanded its definition of bisexuality to include attraction to one’s own and other gender identities, reflecting small but still substantial recent increases in the acceptance in Eurocentric societies (such as Canada and USA) that gender and other identities are best understood across a spectrum. At the same time, we queer folks are exploring our own ways of identifying and describing ourselves in this new context, and we are using a diversity of different words (like bi, bi+, omni, and pan) to do so. So, it isn’t surprising that as use and meaning of the word bisexual has changed over time, there have also been substantial changes in how many people are using this word to describe themselves.

As our use of the term bisexual has increased, so has the amount of research on bisexuality, which seems to have exploded in the early 1990s. We found only 654 academic papers that mentioned bisexuality published between 1900 and 19932 (over more than nine decades!). In the following decade, though, there was a 21-fold increase in the number of papers published (controlling for total number of academic papers published in this same period2). The relative number of papers on bisexuality increased again by 24% between 2003 and 2013, and then by another 77% between 2013 and 2023. Social familiarity with bisexuality, and the interest in doing research on this topic, reflect each other, so we can expect more research to emerge as our societies become more comfortable with nonbinary identities.

Despite these improvements, there is still much less research done on bisexual issues than on those of gay and lesbian people. In the last decade, there was three times as much research done on topics related to gay or lesbian issues than on bisexuality, suggesting only modest improvements relative to the previous two decades (four times and five times as much research on gay and lesbian topics, respectively).

Having said that, we find the research that’s being done on bisexual+ issues to be really exciting. For example, Dr. Brian Feinstein, at Northwestern University, is studying the dating challenges and pressures faced by bi+ folks, while Dr. Lauren Beach, at the same university, is looking at the impacts of social and medical signals on bi+ folks who are living with chronic medical conditions3. The research that is being done has high potential for supporting all of us—as we learn more about bisexuality, we can get better at understanding and resolving the many emotional, health, and discrimination disparities and challenges faced by our community.

We’re optimistic that our societies’ increasing familiarity with bi+ identities, and especially with continuous rather than categorical ideas about genders and sexual identities, will help decrease discrimination against bi+ folks, decrease internalized biphobia that many of us experience, and increase research on bisexuality. But this will be a long process. While we take the time to absorb, reflect on, and share these deep societal changes, there are a few specific steps we can take to improve things in the short term, too. For example, when collecting sensitive information, we should allow folks to self-identify their sexuality, sex and gender using their own words, without prompts (such as providing a blank box to fill in for “sexuality,” rather than using a drop-down menu of options)4. And when we’re answering survey questions ourselves, we can choose to select “another identity not listed above” and provide a written response when we aren’t happy with the identity options made available—the more people do this, the more quickly institutions will adopt diverse and inclusive language.

1 In this essay we use the terms “LGBT” and “bisexual” to mirror those used by the Gallup poll and much of the academic literature. We recognize that these terms do not include all people with same or multigender attraction. U.S. LGBT Identification Steady at 7.2% (gallup.com).

2 Searches using Web of Science Core Collection, April 12 2023. Papers that include the term “bisexual”: 1900-1993 =654 papers (out of 64,396,187 total archived by Web of Science for this time period); 1993-2003 = 2,185 (10,025,113); 2003-2013 = 4,870 (17,990,152); 2013-2023 = 13,696 (28,599,565).

3 Research Spotlight: Drs. Brian Feinstein and Lauren Beach – Bisexual Resource Center (biresource.org).